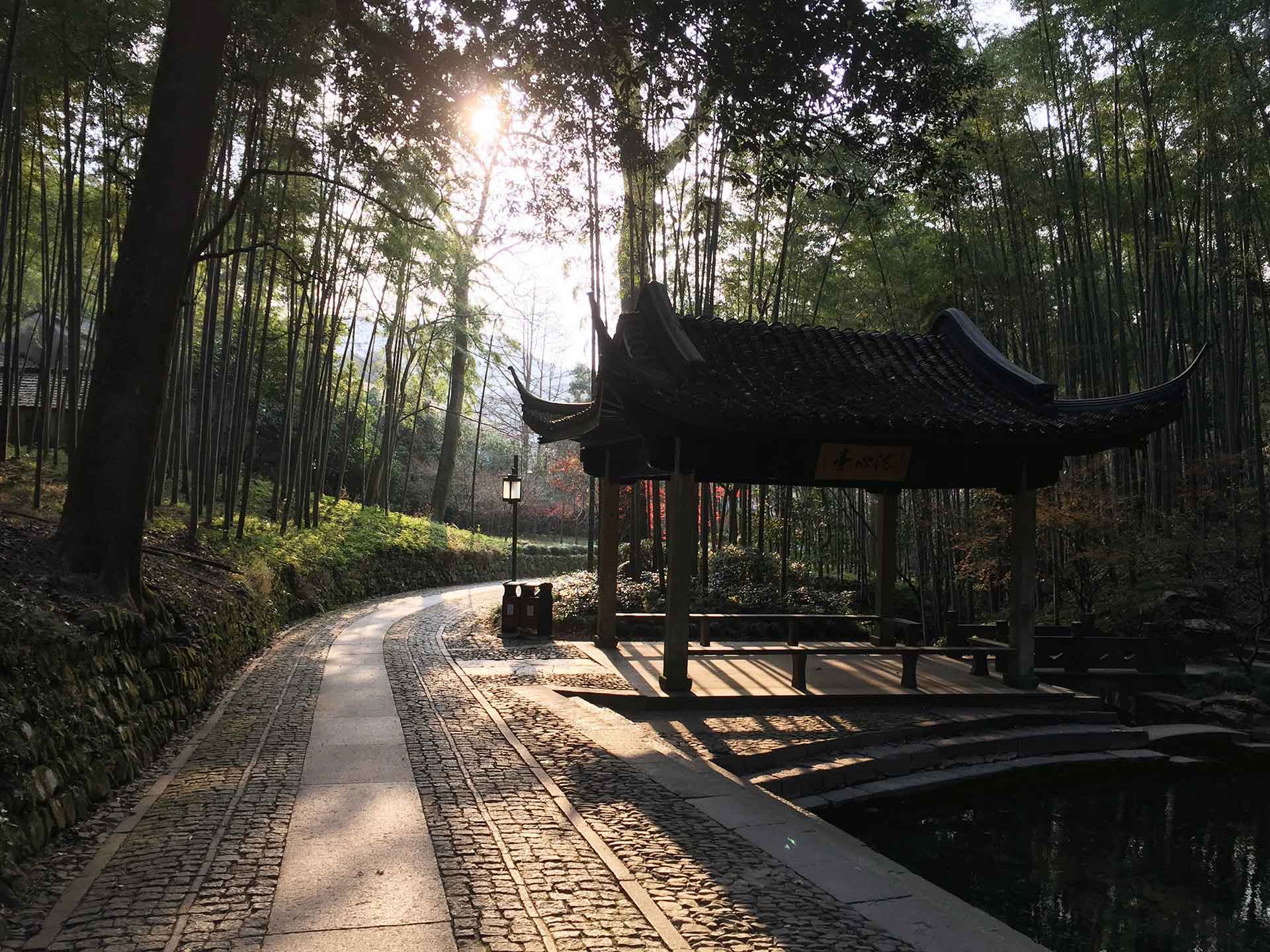

Finding warmth in China, hidden under a slew of bad press and its gruff, sullen veneer.

Curly haired Chinese ladies in puffy vests and mismatched scarves push me backwards at the Hangzhou airport luggage carousel, clucking their tongues in impatience. They are at least half a head shorter than me and middle-aged, but the force of their elbows makes me retreat hastily, even though I am waiting for my bag too.

They grab cardboard boxes off the conveyor belt with ferocity, piling them atop a trolley already heaving with these misshapen lumps. Every time a box arrives, they screech at each other in triumph, high pitched cackles that ring across the arrival hall.

Yes, this is the China that I remember.

China Now

It has been two years since I came to China on a six-week graduation trip, and I am glad to have a reason to be back. This time, fellow travel intern Kenneth and I will explore Hangzhou and Nanjing, on a working holiday cum Scoot campaign. We have been tasked to talk to locals, shoot videos, snap heaps of photos and generate content with one question in mind – what would a Singaporean enjoy doing in China?

That is, if they would even pick China as a holiday destination. Back home, before we learnt of our destination, curious friends would try to guess where I was heading to. “Maybe it’s Japan,” they said hopefully, “or perhaps Korea.”

“Or it might be China,” I’d say, and they’d grimace, offering fair warning about the food, pollution, and the habits of a population 1.3 billion strong. Because who doesn’t know about China’s melamine milk scandal, gutter oil substitute for cooking oil, and the Chinese lady who relieved herself in public at Buona Vista MRT station?

*

We step out of the airport into the chill of winter air, and into a taxi that pulls up almost immediately. It is close to midnight and the roads are near-empty, but we are hungry and ask our driver Song Jian what will be open at this hour. “There are food streets near your hostel,” he says, and proceeds to regale us with all that we can do in Hangzhou, all the tourist sights we must see.

We learn that he is 24, a year younger than us, already father to a one-year-old son. He will ply the streets until three am as he does every night, and then go home to his family. “But sometimes I knock off at one or two to go home early,” he says, and I hope our cab fare across the city will be reason enough for him to do so tonight.

Close to our hostel we find a supper spot, a stall selling grilled skewers of meat, seafood and vegetables, still thronging with patrons knocking back Chinese beer and liquor at one in the morning. We pick out the items we want, under the watchful eye of a gruff looking man with cigarette-blackened teeth and a thinning hairline. I am hesitant as I ask the prices of every single item I pick up, afraid he will berate me for wasting his time.

(See also: What to eat in Hangzhou and Nanjing)

“Where are you from?” he asks hoarsely, my accent evident that I am not local. “Singapore,” I respond, and he grins lopsidedly, giving us a thumbs up.

His is the veneer that many Chinese wear, brusque efficiency and an unsmiling mien. Few people are friendly at first blush, at least not in the effusive welcoming way of the Taiwanese, or the genteel politeness of the Japanese.

But we warm to each other slowly, uniting over physical exertion that tourist attractions demand of us – such as Sun Yat Sen’s mausoleum in Nanjing, located atop a 392-step climb. When we finally make it up I sit on the top step for a breather, offering words of encouragement to spritely old women who don’t look too different from the ones I encounter at the airport on day one. “加油,你们到了!” is all I can manage with in Mandarin, but it is enough to elicit a smile and a wave.

*

Not every encounter is as pleasant. At popular chain restaurant Grandma’s House, a well-dressed young mother at the next table hacks loudly and spits on floor, and when she leaves her phlegm is still glistening on black shiny marble tiles. I lose count of the number of people who do this on the streets, out of car windows, at tourist spots.

At Hangzhou’s West Lake I am about to lower myself onto a rock to rest when I spot a puddle of fresh sputum in a crevice. In Nanjing one morning, I am souvenir shopping along the pedestrian streets surrounding Confucius Temple when I miss a step, and it sends me tumbling to the pavement. There are people around, but they stare from a distance, and no one comes to help. While picking myself up I catch sight of another ubiquitous phlegm puddle two feet away, and am instantly grateful I did not land there.

And then I think, if my friends could see me now, who would believe that this country is as lovely as I always claim it to be?

*

Shebana Coelho writes: “When you travel, you tend to cultivate a persona different from that of your everyday life. You’re open to everything, and you take better care of yourself emotionally. Because you know that you’re out of your comfort zone, away from home, you work on letting go of whatever you can so that you can move with ease.”

I always struggle to explain what it is I love about China. Coelho was writing about Mongolia when she penned the above passage, but she could be referring to anywhere in the world that is challenging. Slowly I realise how much I let go of when I am in China, all the things that would irk me in everyday life that I let slide here. On the train I am shoved aside when people want to alight; when its doors open passengers jostle their way past me before I can take a step out. But this is their country, and if I expect visitors to Singapore to smoke in yellow boxes and not litter, can I really complain if they do as they please at home?

So I learn to move with ease, to ebb and flow as I readjust to China’s norms. I hold my tongue when my patrons of favourite dumpling shop insist on smoking indoors, and fill the enclosed space with noxious fumes.

On the overnight train from Hangzhou to Nanjing, strands of hair from previous occupants cling to my pillow, which is limp and grey from use. Back home I’m sure this would bother me, but now I pick them off, pull up my hoodie, and climb into bed.

The train moves off, rocking and swaying along the tracks, in a back and forth motion that quickly lulls me to sleep. Outside the landscape changes from city to industry, factories that spew columns of dark smoke and rivers curdled with green algae, and farmers growing small vegetable plots beside them. I tell myself to let go of judgement, distaste, disgust. For the people living here, this landscape is home. And I will be back to see more.

(See also: How to travel Hangzhou and Nanjing like a local)

Like what you’re seeing? Share, like, subscribe and follow more of our adventures on Facebook or Instagram!